Hurumph! Earning a living gets in the way of writing.

Rabu, 31 Agustus 2011

Sabtu, 27 Agustus 2011

The Green Man a.k.a. Leafy George

It's been a while between blogs because we've had a few visitors to the Burman place recently, which always involves considerably more eating and drinking than usual, on the one hand, but less opportunity and motivation to sit at a keyboard, on the other. In fact, there's probably a Maths or Physics law to describe the inverse relationship between the two events: as the amount of time and energy spent on eating and drinking increases, so does the amount of time and energy spent on all other activities proportionally decrease - something like that.

Anyway, I was taking 20 minutes away from being a charming and sociable host yesterday, and ended up having an E.M.Forster moment.

I remember reading of E.M.Forster's surprise when he learned that Rooksnest - the house he grew up in, and which he used as the setting for Howards End - had, before the Forsters moved in, been known as Howards for many years. Instead of creating the name from his imagination, his subconscious had dredged it from forgotten memories (if that isn't a contradiction in terms).

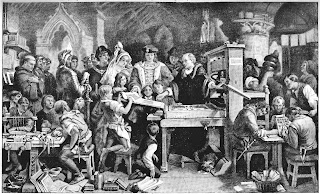

Which is similar to my moment. In writing The Snowing and Greening of Thomas Passmore, I thought I'd had little connection with or knowledge of The Green Man (also known as Leafy George) prior to researching this motif for the novel in the early noughties. However, as I was sifting through a box of cards that I'd collected many years ago, which I hadn't properly looked at since emigrating to Australia 21 years ago, I came across a Christmas card with this wonderful image that must have been loitering in a corner of my subconscious all that time. Handwritten on the back of the card is the following credit: Green Man by Aysha © 1986

Kamis, 18 Agustus 2011

Recent reads: In the Miso Soup by Ryu Murakami

While I've raved often about the work of Haruki Murakami, a friend (visit his blog) suggested I try Ryu Murakami and, for starters, In the Miso Soup.

'It's just before New Year, and Frank, an overweight American tourist, has hired Kenji to take him on a guided tour of Tokyo's nightlife. But Frank's behaviour is so odd that Kenji begins to entertain a horrible suspicion: his client may in fact have murderous desires. Although Kenji is far from innocent himself, he unwillingly descends with Frank into an inferno of evil, from which only his sixteen-year-old girlfriend, Jun, can possibly save him.'(Bloomsbury, translated by Ralph McCarthy)

This is a relatively short, three-part novel (180 pages), and it's fair to say that my responses to it changed with each part. Part One captured my attention largely because of the descriptions of Tokyo nightlife; Murakami takes the reader on a neon-illuminated tour of Tokyo's seedier nightclubs and peepshows, providing us with an intriguing view of the sex industry - at least, selected aspects of it - before leading us to a baseball batting centre ('a surreal open space illuminated by fluorescent lights'). As for the characters leading this tour, I felt unconvinced and irritated by Kenji's intuitions about Frank's murderous nature, and wished that he'd stop his whining and get on with the job he'd taken or abandon the unlikeable Frank and go find, Jun, his girlfriend.

In Part Two, with blood pooling at the edge of each page, we meet the darker side of Frank. Though it felt like overkill to me in every sense, and I nearly finished with the book on a couple of occasions, it was towards the end of this part that Kenji's inability to detach himself from events began to pique my interest.

However, the third and final part completely won me over and made me glad I stayed for the entire macabre experience. Frank and Kenji came fully alive for me and I found myself wanting to find out what was going to happen to them. (It's when I just don't care that I know a novel hasn't worked for me).

What added considerably to my appreciation of this novel, though, is that, by chance, I followed my reading of it with Robert Louis Stevenson's Gothic horror Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The similarities between Frank and Mr Hyde are startling, despite one being large and the other being 'dwarfish' and 'troglodytic'. They are both malformed, malevolent and given to murderous rage, and there are qualities about their appearance (the feel of Frank's skin, the foul soul that ... transpires through, and transfigures, [Hyde's] clay continent) which both narrator's find difficult to pin down and articulate. Kenji is a modern Mr Utterson, although the path he travels is much more perilous.

All up, In the Miso Soup is a novel I'm glad I read, and I'll be picking up another Ryu Murakami before too long.

Senin, 15 Agustus 2011

The Transvaal Irish and Irish American Brigades

There were 2 brigades which were combined just before deployment to Zandspruit - the Transvaal Irish Brigade under John McBride who represented the growing Irish nationalism of the time, and the Irish American Brigade which was a Clan na Gael New Movement styled brigade of just under 300 men. This is the brigade which was placed under John Blake whose Irish heritage is near nonexistent.... read further.

The Dawn Torch

This allegory is dedicated to my niece who is the last female in our family line and to all women in troubled times. It was first published in a Woman's Book of Allegory and then as a promotional piece on RedBubble.

THE WATCHERS

Soon, too soon the time will come when knowing that you are not alone is going to mean the difference between the will to fight on and the temptation to give in. You live, you see, in that grey-light hour just before dawn when all creatures despair.

My name is Anna. I am from the cusp between the sunset of women’s traditions and the dawn of the war gods. I am your most direct ancestor at the Watch. We have been drawn together to witness the passing of an era.

Our sister, the Modjaji, faces her choice today. The beginning and end of our traditions are contained within the choice we make. Each of us understands the choice the other has to make. Each will make that choice in her own time.

ANNA

My gift to you is understanding. We are free, thinking elements in a dance which creates and powers the universe. We dance in our own time, in our own space, but there is only one dance that encompasses all times and all places. Neither dance nor its purpose is tangible. This intangibility is what we call the sacred.

I was born in Ayrshire on Temple lands in the hidden valley. At five I was sent to Our Lady’s shelter near Rouen in France to train as a handmaiden. After ordination I served in the house of a Knight.

The festival of fire came early in the year I died. I stood on the banks of the river at the appointed hour and chanted the opening blessing as worshippers looked on. The prayer should have been accepted. It was not.

Angry waves rushed across the estuary, sucking and pulling me into the sand. I panicked and fled to dry ground, but the waters followed. When the fury abated it took the freshly sown seeds with it. My Lord Knight blamed me and ordered my burning.

My daughter’s nurse fled, taking my child with her.

I was dragged from the temple where I fought off my attackers. As a warrior-priestess I was as comfortable with a sword as with a prayer.

I was dragged from the temple to the town by my arms; my legs and body shredded by shrubs and rocks. They hauled me through the streets like meat to slaughter.

I was jeered by those who only hours before would have knelt in front of me begging a gift of healing for this or that relative.

I was thrown into the basement of the guard house. My right hip snapped like a dry, autumn leaf as I hit the unyielding floor. I thought the pain would kill me as I lay upon the seeping, chilled slabs.

That day I watched the cloudless sky through the grate which emptied onto the town square. I listened to the hollow thud of hammers nailing my pyre into place.

The only moisture I received was the spittle from passersby. The only comfort I had was that no peasant thrust the dismembered body of my daughter through the prison bars.

I was pulled from the room just before dawn. If there was pain I no longer felt it. I was cold and numb and I thought only of my thirst. They tied me to the scaffolding and piled wood about my legs. Then they torched me.

Suddenly, I did not want to die. Suddenly, the unfairness of it all closed about me and I screamed. This was no helpless protest, no sound of pain or fear. My scream had meaning and strength and the curse spiraled up from a fire more red hot than the one that ate away my flesh and turned my bones black.

I cursed my lord Knight. I cursed him whom I loved and served. I felt the Watchers swell inside me. I felt them reclaim the curse, draw it out as one drags a net through the waters of the river and empties it onshore.

I died without hatred in my soul. That night the peasants gathered my ashes and placed them in a sack. They carried the ashes into the forest, to a grave among the trees. There the peasants lost heart, flooded by inexplicable remorse and superstition, frightened by the darkness about them where curious creatures flitted at the edge of their torch light.

A few days later my servants crept from hiding and filled in the grave.

THE MODJAJI

The war gods have swept away her kingdom. In its time this was a great kingdom.

When your time comes to choose I want you to remember today. I want you to draw on the quiet courage played out among those who begin the process of passing on the torch.

Listen, now! The harbor rasps as ships rub against jetties.

The Modjaji stands on the temple balcony, do you see, with its uninterrupted view of the harbor. She is the Rain Queen around whom a religion has gathered, trapping her in its form and formula.

Do you see how she watches that ship carve the sea in two? She shields her eyes from the dawn with soft hands. Her wrists arch downwards, freed from the sleeves of the caftan playing across her feet. The caftan was spun in Egypt, its color the green of good rains. There have been no good rains in this priestess’ lands, not for a very long time.

Her expression is caught between envy and resignation. If she could she would swim to the ship, hide below deck and flee her fate. Her eyes move from the ship to the gathering clouds but she forces herself back into the temple. She knows the end is near and every act has become an act of will.

Do you see the girl hesitating on the stairs outside the temple door? That is Deni, the Modjaji-in-waiting. She is also the Modjaji’s blood daughter.

The Modjaji serves a celibate religion filled with isolation and loneliness. We do not judge her, but the Modjaji judges herself. She believes that her little indiscretion is the cause of the catastrophe she faces. She blames herself for the lack of rain.

Mbire is her chief adviser. None of us remember the exact day on which he sold his soul to the darkness. He trained in Egypt and he sends his apprentices to his old master. He has a cadre of sorcerers ready to rise up against the Modjaji, but she still has allies in Mbire’s palace.They will save Deni.

The clouds have gathered each day during the rain season, laughed at the parched earth and skittered away.

The horizon is different today.

The clouds churn across the landscape towards the city. They carry within the power of raging torrents. The earth is too hard. It will not swallow the storm water.

The Modjaji has prepared Deni for flight but, as you see, the girl still hesitates outside the temple door. The Modjaji has returned from the balcony to speak with her again.

You must be out of the city by noon, Deni, the Modjaji says. Do you remember the way?

So soon? Deni replies.

The trap door is beneath the kitchen. The passage leads to the ruined temple. At the end of the passage is a door that opens onto the side of the hill, away from the city. Move across the fields to the forest. From there travel along the coast southward.

I cannot leave you, Modjaji.

Move the servants through the fields even if they are waste deep in water. You must be in the forest before Mbire knows you are gone.

I cannot leave you.

Deni, I will always be with you, replies the Modjaji.

*

Smell the rain as it rushes towards the temple and the city. There is thunder in the distance.

The Modjaji hears footsteps on the stairs. She sits down on the oracle’s mat and waits. An old man enters. He is dressed like a shepherd but carries himself like a warrior.

He asks, Do you not want me to stay?

I am not afraid, replies the Modjaji.

The old man brushes his hand against her hair.

Do not die with regret in your soul, he says.

*

Clouds snap into place with military precision. Hailstones plummet to earth. When the storm passes children cry for their parents crushed beneath mud and brick and beam.

See how Mbire delays his conquest of the temple. Remorse is not a reason. Mbire is beyond remorse. In the secret most place of his heart he fears her.

Finally, Mbire climbs the spiral stairs to the temple. He pants, do you see?

The cedar door is closed. He pulls at the iron handle but it is wedged on the inside. He heaves his body against the door. He begins to hammer his fists on the wood like a spoiled child.

The Modjaji listens. She is dispassionately amused.

Sunset drops onto the rubble and ruin of the last great city of the Rain Queen. The Modjaji lights the oil lamps. Her shadow dances and curtsies, bumps and frolics.

She takes a libation cup onto the balcony, faces west and raises the cup to her lips. She drinks. Moving swiftly, the Modjaji returns to the temple, placing a bottle of wine and a clay cup beside the oracle’s fire that has died down to remnants and embers.

She returns to her mat and lies down, her head facing west, her feet facing east from where the new dawn will rise. We will gather her to us. She has been faithful.

Mbire breaks down the temple door. He kicks the body of the Modjaji like a man kicks a chained dog. He drinks the poisoned wine from the most holy of cups.

He becomes disembodied regret.

DENI

We cannot choose for our sisters, but once they make their choice we become the guardians and keepers of their choices.

Deni has been packing a bag of herbs for the escape from the temple. Her selection is practical. She carries remedies for sprains and strains, coughs and fevers. She leaves the storeroom and slips into the temple compound, stooping briefly to pick a few fresh leaves for her bag. They will wilt, she knows, but their essence will remain strong.

As she straightens she sees a pod of sorcerers approaching.

The part of Deni that is still a child hears the cook's scream, begging her to run, to flee. But the novice who would have been the Modjaji throws her bag to the side, anchors her feet, knees slightly bent, back straight. She feels her arms gather buoyancy at her sides. She waits, still as a stone.

The air hums and something granite grey stands where Deni once stood. The sorcerers are not deceived. They know what they face. They approach slowly but without hesitation.

A sorcerer bows, touching first his forehead then his lips then his heart with the fingers of his left hand.

Modjaji, he says.You remember me. I am Mungo. We played together as children.

*

The refugees move beneath the city. The air about them is damp and their feet slide on the wet floor of the tunnel.

Near midnight the sorcerers’ fingers search for the key to the door. When it opens, the door slides easily. They tumble onto the hillside close to the stone which marks the path.

Heat wraps itself around the refugees. Panic ripples through them as they stumble onto the forest fringe.

The forest turns to marshland and women throw themselves into the shallows, splashing their faces and scooping the brine water into their children’s mouths.

Not far from where they paddle Deni sees an outcrop of stone. That is where they will hide until the soldiers stop looking for them.

For ten days the refugees huddle in the caves. On the evening before they leave Mungo enters the sanctuary where Deni sits. He drops down beside her on the oracle mat and hands her a bowl of broth. They sit without speaking until the broth dulls her pain. Mungo breaks the silence saying, This is no time for remorse, Modjaji.

As if awakened by the title, Deni laughs bitterly.

No, she says. I do not deserve the title, sorcerer. I have no hope to give these people, no religion to drug their minds.

Mungo takes her hand in his. Leaning back against the cave wall he stares at the bleak visions which play among the shadows. Seek the hope in your soul, Mistress, he says. It is there. I would follow you into death and beyond.

THE TORCH CARRIER

The last Modjaji died in her temple. She tricked her enemy into dying with her. She did not, could not stop the new epoch but her daughter Deni could survive it.

Mungo and Deni turned their prayers and spells to the future; to weave the path along which their children would carry the torch. Mungo and Deni had six children. Their eldest son traveled to Egypt and entered the pharaoh’s service. His son became a scribe and he, in turn, fathered a line of scribes who migrated across the Mediterranean.

One served in Hannibal’s army. He deserted and traveled to Spain where he married a merchant’s daughter. We are descended from his line.

The torch has not passed from mother to daughter. Nor has it moved down the same branch of our family. These routes would be too obvious, too dangerous. The torch has crisscrossed through our bloodline like an assassin’s knife slicing the darkness here or there.

Its passage has been a torturous, circuitous one watched over by us; hidden, hounded, discovered, betrayed, savaged and saved. Each carrier is ignorant of her burden.

We act on the premise that what humans do not recognize they cannot betray.

*

You are different.

You had the potential to inherit the torch, but we intercepted its passing at your birth.

The space where the torch should lie within you is empty and that emptiness gnaws at you like a dog with an insatiable hunger gnaws at a bone.

You must consciously accept the torch from us. You, like I before you, live within the cusp of two epochs. You live not at the end of an era as I did, but at the beginning of one. Cusps are active points of choice.

We cannot force you to take the torch, to hold it up against the terror of the predawn darkness you face. We can only offer you the choice. You must take the torch of your own free will, as an act of faith in hope.

If you do not accept the torch it will pass to another epoch where women are destined to shape their world.

If you accept the torch, know this.

Women’s power is strongest when exercised collectively. Each day you nurture the flame, each day you inch it higher into the sky, other women will be raising their torches. Slowly, inexorably, you will thread a net from horizon to horizon and capture the light of the new dawn.

If you choose hope.

THE WATCHERS

Soon, too soon the time will come when knowing that you are not alone is going to mean the difference between the will to fight on and the temptation to give in. You live, you see, in that grey-light hour just before dawn when all creatures despair.

My name is Anna. I am from the cusp between the sunset of women’s traditions and the dawn of the war gods. I am your most direct ancestor at the Watch. We have been drawn together to witness the passing of an era.

Our sister, the Modjaji, faces her choice today. The beginning and end of our traditions are contained within the choice we make. Each of us understands the choice the other has to make. Each will make that choice in her own time.

ANNA

My gift to you is understanding. We are free, thinking elements in a dance which creates and powers the universe. We dance in our own time, in our own space, but there is only one dance that encompasses all times and all places. Neither dance nor its purpose is tangible. This intangibility is what we call the sacred.

I was born in Ayrshire on Temple lands in the hidden valley. At five I was sent to Our Lady’s shelter near Rouen in France to train as a handmaiden. After ordination I served in the house of a Knight.

The festival of fire came early in the year I died. I stood on the banks of the river at the appointed hour and chanted the opening blessing as worshippers looked on. The prayer should have been accepted. It was not.

Angry waves rushed across the estuary, sucking and pulling me into the sand. I panicked and fled to dry ground, but the waters followed. When the fury abated it took the freshly sown seeds with it. My Lord Knight blamed me and ordered my burning.

My daughter’s nurse fled, taking my child with her.

I was dragged from the temple where I fought off my attackers. As a warrior-priestess I was as comfortable with a sword as with a prayer.

I was dragged from the temple to the town by my arms; my legs and body shredded by shrubs and rocks. They hauled me through the streets like meat to slaughter.

I was jeered by those who only hours before would have knelt in front of me begging a gift of healing for this or that relative.

I was thrown into the basement of the guard house. My right hip snapped like a dry, autumn leaf as I hit the unyielding floor. I thought the pain would kill me as I lay upon the seeping, chilled slabs.

That day I watched the cloudless sky through the grate which emptied onto the town square. I listened to the hollow thud of hammers nailing my pyre into place.

The only moisture I received was the spittle from passersby. The only comfort I had was that no peasant thrust the dismembered body of my daughter through the prison bars.

I was pulled from the room just before dawn. If there was pain I no longer felt it. I was cold and numb and I thought only of my thirst. They tied me to the scaffolding and piled wood about my legs. Then they torched me.

Suddenly, I did not want to die. Suddenly, the unfairness of it all closed about me and I screamed. This was no helpless protest, no sound of pain or fear. My scream had meaning and strength and the curse spiraled up from a fire more red hot than the one that ate away my flesh and turned my bones black.

I cursed my lord Knight. I cursed him whom I loved and served. I felt the Watchers swell inside me. I felt them reclaim the curse, draw it out as one drags a net through the waters of the river and empties it onshore.

I died without hatred in my soul. That night the peasants gathered my ashes and placed them in a sack. They carried the ashes into the forest, to a grave among the trees. There the peasants lost heart, flooded by inexplicable remorse and superstition, frightened by the darkness about them where curious creatures flitted at the edge of their torch light.

A few days later my servants crept from hiding and filled in the grave.

THE MODJAJI

The war gods have swept away her kingdom. In its time this was a great kingdom.

When your time comes to choose I want you to remember today. I want you to draw on the quiet courage played out among those who begin the process of passing on the torch.

Listen, now! The harbor rasps as ships rub against jetties.

The Modjaji stands on the temple balcony, do you see, with its uninterrupted view of the harbor. She is the Rain Queen around whom a religion has gathered, trapping her in its form and formula.

Do you see how she watches that ship carve the sea in two? She shields her eyes from the dawn with soft hands. Her wrists arch downwards, freed from the sleeves of the caftan playing across her feet. The caftan was spun in Egypt, its color the green of good rains. There have been no good rains in this priestess’ lands, not for a very long time.

Her expression is caught between envy and resignation. If she could she would swim to the ship, hide below deck and flee her fate. Her eyes move from the ship to the gathering clouds but she forces herself back into the temple. She knows the end is near and every act has become an act of will.

Do you see the girl hesitating on the stairs outside the temple door? That is Deni, the Modjaji-in-waiting. She is also the Modjaji’s blood daughter.

The Modjaji serves a celibate religion filled with isolation and loneliness. We do not judge her, but the Modjaji judges herself. She believes that her little indiscretion is the cause of the catastrophe she faces. She blames herself for the lack of rain.

Mbire is her chief adviser. None of us remember the exact day on which he sold his soul to the darkness. He trained in Egypt and he sends his apprentices to his old master. He has a cadre of sorcerers ready to rise up against the Modjaji, but she still has allies in Mbire’s palace.They will save Deni.

The clouds have gathered each day during the rain season, laughed at the parched earth and skittered away.

The horizon is different today.

The clouds churn across the landscape towards the city. They carry within the power of raging torrents. The earth is too hard. It will not swallow the storm water.

The Modjaji has prepared Deni for flight but, as you see, the girl still hesitates outside the temple door. The Modjaji has returned from the balcony to speak with her again.

You must be out of the city by noon, Deni, the Modjaji says. Do you remember the way?

So soon? Deni replies.

The trap door is beneath the kitchen. The passage leads to the ruined temple. At the end of the passage is a door that opens onto the side of the hill, away from the city. Move across the fields to the forest. From there travel along the coast southward.

I cannot leave you, Modjaji.

Move the servants through the fields even if they are waste deep in water. You must be in the forest before Mbire knows you are gone.

I cannot leave you.

Deni, I will always be with you, replies the Modjaji.

*

Smell the rain as it rushes towards the temple and the city. There is thunder in the distance.

The Modjaji hears footsteps on the stairs. She sits down on the oracle’s mat and waits. An old man enters. He is dressed like a shepherd but carries himself like a warrior.

He asks, Do you not want me to stay?

I am not afraid, replies the Modjaji.

The old man brushes his hand against her hair.

Do not die with regret in your soul, he says.

*

Clouds snap into place with military precision. Hailstones plummet to earth. When the storm passes children cry for their parents crushed beneath mud and brick and beam.

See how Mbire delays his conquest of the temple. Remorse is not a reason. Mbire is beyond remorse. In the secret most place of his heart he fears her.

Finally, Mbire climbs the spiral stairs to the temple. He pants, do you see?

The cedar door is closed. He pulls at the iron handle but it is wedged on the inside. He heaves his body against the door. He begins to hammer his fists on the wood like a spoiled child.

The Modjaji listens. She is dispassionately amused.

Sunset drops onto the rubble and ruin of the last great city of the Rain Queen. The Modjaji lights the oil lamps. Her shadow dances and curtsies, bumps and frolics.

She takes a libation cup onto the balcony, faces west and raises the cup to her lips. She drinks. Moving swiftly, the Modjaji returns to the temple, placing a bottle of wine and a clay cup beside the oracle’s fire that has died down to remnants and embers.

She returns to her mat and lies down, her head facing west, her feet facing east from where the new dawn will rise. We will gather her to us. She has been faithful.

Mbire breaks down the temple door. He kicks the body of the Modjaji like a man kicks a chained dog. He drinks the poisoned wine from the most holy of cups.

He becomes disembodied regret.

DENI

We cannot choose for our sisters, but once they make their choice we become the guardians and keepers of their choices.

Deni has been packing a bag of herbs for the escape from the temple. Her selection is practical. She carries remedies for sprains and strains, coughs and fevers. She leaves the storeroom and slips into the temple compound, stooping briefly to pick a few fresh leaves for her bag. They will wilt, she knows, but their essence will remain strong.

As she straightens she sees a pod of sorcerers approaching.

The part of Deni that is still a child hears the cook's scream, begging her to run, to flee. But the novice who would have been the Modjaji throws her bag to the side, anchors her feet, knees slightly bent, back straight. She feels her arms gather buoyancy at her sides. She waits, still as a stone.

The air hums and something granite grey stands where Deni once stood. The sorcerers are not deceived. They know what they face. They approach slowly but without hesitation.

A sorcerer bows, touching first his forehead then his lips then his heart with the fingers of his left hand.

Modjaji, he says.You remember me. I am Mungo. We played together as children.

*

The refugees move beneath the city. The air about them is damp and their feet slide on the wet floor of the tunnel.

Near midnight the sorcerers’ fingers search for the key to the door. When it opens, the door slides easily. They tumble onto the hillside close to the stone which marks the path.

Heat wraps itself around the refugees. Panic ripples through them as they stumble onto the forest fringe.

The forest turns to marshland and women throw themselves into the shallows, splashing their faces and scooping the brine water into their children’s mouths.

Not far from where they paddle Deni sees an outcrop of stone. That is where they will hide until the soldiers stop looking for them.

For ten days the refugees huddle in the caves. On the evening before they leave Mungo enters the sanctuary where Deni sits. He drops down beside her on the oracle mat and hands her a bowl of broth. They sit without speaking until the broth dulls her pain. Mungo breaks the silence saying, This is no time for remorse, Modjaji.

As if awakened by the title, Deni laughs bitterly.

No, she says. I do not deserve the title, sorcerer. I have no hope to give these people, no religion to drug their minds.

Mungo takes her hand in his. Leaning back against the cave wall he stares at the bleak visions which play among the shadows. Seek the hope in your soul, Mistress, he says. It is there. I would follow you into death and beyond.

THE TORCH CARRIER

The last Modjaji died in her temple. She tricked her enemy into dying with her. She did not, could not stop the new epoch but her daughter Deni could survive it.

Mungo and Deni turned their prayers and spells to the future; to weave the path along which their children would carry the torch. Mungo and Deni had six children. Their eldest son traveled to Egypt and entered the pharaoh’s service. His son became a scribe and he, in turn, fathered a line of scribes who migrated across the Mediterranean.

One served in Hannibal’s army. He deserted and traveled to Spain where he married a merchant’s daughter. We are descended from his line.

The torch has not passed from mother to daughter. Nor has it moved down the same branch of our family. These routes would be too obvious, too dangerous. The torch has crisscrossed through our bloodline like an assassin’s knife slicing the darkness here or there.

Its passage has been a torturous, circuitous one watched over by us; hidden, hounded, discovered, betrayed, savaged and saved. Each carrier is ignorant of her burden.

We act on the premise that what humans do not recognize they cannot betray.

*

You are different.

You had the potential to inherit the torch, but we intercepted its passing at your birth.

The space where the torch should lie within you is empty and that emptiness gnaws at you like a dog with an insatiable hunger gnaws at a bone.

You must consciously accept the torch from us. You, like I before you, live within the cusp of two epochs. You live not at the end of an era as I did, but at the beginning of one. Cusps are active points of choice.

We cannot force you to take the torch, to hold it up against the terror of the predawn darkness you face. We can only offer you the choice. You must take the torch of your own free will, as an act of faith in hope.

If you do not accept the torch it will pass to another epoch where women are destined to shape their world.

If you accept the torch, know this.

Women’s power is strongest when exercised collectively. Each day you nurture the flame, each day you inch it higher into the sky, other women will be raising their torches. Slowly, inexorably, you will thread a net from horizon to horizon and capture the light of the new dawn.

If you choose hope.

Kamis, 11 Agustus 2011

New article for The View From Here

It's been a few months since I wrote anything for The View From Here, so thought I should get my two fingers out (you'll see what I mean) and write something.

You can read What every chicken should know about Cupertino here.

Senin, 08 Agustus 2011

400 words

As a writer my vision of the world is confined to 400 words, not by my own choice but by the constraints of the places I publish.

Life in 400 words, 400 well-chosen words each needing to convey a universe of meaning so that the story I tell reads like it is composed of 4 000 words.

400 words are tiring. 400 words take more time than finding 4 000. 400 words is crafting my art to a hair’s breadth of perfection, and scary too, because most people think 400 words are so easy to write.

Life in 400 words, 400 well-chosen words each needing to convey a universe of meaning so that the story I tell reads like it is composed of 4 000 words.

400 words are tiring. 400 words take more time than finding 4 000. 400 words is crafting my art to a hair’s breadth of perfection, and scary too, because most people think 400 words are so easy to write.

Minggu, 07 Agustus 2011

Listening to The Waifs

Have been listening to a fair bit of The Waifs recently. They've been a favourite Australian band of mine for many years, but I've been giving their CDs a renewed hammering of late. Songs I particularly like are The Haircut, Service Fee (both from Sink or Swim) and the slow version of Without You (from sundirtwater). Having painted those lighthouse steps recently (see second last post), thought this might be appropriate: Lighthouse.

Kamis, 04 Agustus 2011

Down at the Factory of the Imagination in July

Some might say all's not well down at the Factory of the Imagination, on account of there having only been 5,000 words added to Number Three novel this month, instead of the 10,000 target (see previous post). And yet it feels as though I've written four times that amount ... at least. Honest guv.

Let me assure you, the cogs have not been idle; there's been no strikes, no working-to-rule nor go-slows in this factory. I've been labouring over a transition sequence from one main course of the story to the next, but it seems to have taken forever-and-a-day.

I was wondering how to explain this shortage of finished words, during a rare lunch break, and found myself wandering into the kitchen of the Works Canteen.

Cook was reducing a sauce, to serve with the day's speciality: Bœuf à la Métaphore. To make the sauce, the carcasses of ten Aberdeen Anguses (grazed on a diet of organic grain, stout and whiskey) had been boiled in several casks of red wine to form a vat of rich broth, which, over a period of three days, was being reduced to the amount of two and a half cups. Although I'm a vegetarian, and Cook likes to spit at me for this, I was assured that, so potently delicious is it, that a mere sniff of the finished sauce would instantly repair my damaged soul and convert me into a raging carnivore once more.

This, I realised, is what I'd been attempting to do with words across the last four weeks. I'd write a few hundred, and then reduce those to fifteen or twenty, and then, on the following day, I'd further reduce them to seven or eight. I'd struggle to dice in another couple of hundred words, but would then start stirring them around again, simmering over them, until only a thimbleful were left. And so on and so on. What feels like 40,000 words reduced to 5,000.

And there I have my excuse. My explanation. Surely I deserve a bonus, instead of getting my pay docked?

Burnt gravy, anyone?

Senin, 01 Agustus 2011

Winter weekend, art, and a competition

This coming weekend sees another of my home town's Winter Weekend celebrations. Throughout the winter months, every year, Port Fairy hosts a number of events, except I've gone and got myself involved this time. I didn't mean to. It just sort of happened.

While you can see the range of events taking place for this culinary-inspired weekend here, I rashly agreed to participate in the Smorgasbord of Port Fairy Art exhibition - a mosaic of paintings, depicting fragmented scenes of the town, which will be the subject of a competition (guess the layout of the mosaic). Twenty local artists were invited to choose one of twenty photos as the basis for a small painting (40 x 30cm), which will then be arranged as a mosaic. The photos, as chosen by each artist, can be found with details of the competition here, but that's my photo above.

I must confess, this has caused me some angst and I would have destroyed my effort several times over if I hadn't made a commitment. It may have been significantly smaller than the piece I put together for this year's Biblio-Art Exhibition (and I blogged about that and my nod to Jeffery Smart right here), but I found this one considerably harder. Nonetheless, I learned a bit along the way and played around with different brush strokes, so, while I wouldn't hang it on my wall, I'm happy to pin it up here for the time-being.

Langganan:

Komentar (Atom)